| |

Loss of the Ship

11. THE GROUNDING

Their position might now seem to be just a question

of raw tug pulling power against the strength of the stream. But if

you narrow a channel of flowing water it just flows more quickly and

generates more turbulence and stronger eddies. That is why broad, calm

rivers suddenly turn into boiling maelstroms where the banks narrow.

The broad area of Strait above the Suspension Bridge was already seriously

narrowed by the encroaching shoreline and the piers of the Suspension

Bridge thus speeding the flow of water under the Suspension Bridge.

Conway and her tugs were now actually acting like a plug and further

narrowing the channel making the stream flow even faster around the

ship and further compounding the eddies and turbulence. The harder the

ship was pulled the worse it got. The treatment was killing the patient!

Their position might now seem to be just a question

of raw tug pulling power against the strength of the stream. But if

you narrow a channel of flowing water it just flows more quickly and

generates more turbulence and stronger eddies. That is why broad, calm

rivers suddenly turn into boiling maelstroms where the banks narrow.

The broad area of Strait above the Suspension Bridge was already seriously

narrowed by the encroaching shoreline and the piers of the Suspension

Bridge thus speeding the flow of water under the Suspension Bridge.

Conway and her tugs were now actually acting like a plug and further

narrowing the channel making the stream flow even faster around the

ship and further compounding the eddies and turbulence. The harder the

ship was pulled the worse it got. The treatment was killing the patient!

|

|

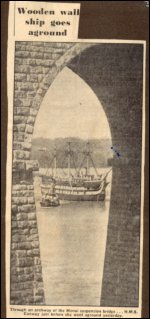

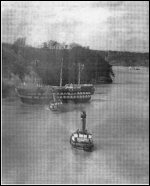

Captain Durrant, watching from the Suspension Bridge, was under no illusions about the dangers, not just to Conway but to his two tugs and their crews. In many respects the tugs and their crews were now in greater danger than those on the relative safety of the ship, He reported to the committee that "Dongarth, held head and stern by tow ropes, was severely hampered in her manoeuvring ability, and at one point was listed to her gunwale in her efforts to hold Conway up to wind and tide".[5] This is very evident in the following photos.

According to the Ship's Log at 10.09 am[12] the pilot boat secured herself to port (the right side looking at the photos) to give extra power. Rather like an ant pushing an elephant. However this time cannot be correct as it was before the above sequence of events and the pilot boat is clearly not alongside in any of the above photos. The pilot boat must have come alongside at approximately 10.20am as the photos taken after that time do show her in position.

|

|

|

Captain Durrant recounts the rest of the saga. "At 10.30 am, without warning, when Conway was abreast of Platters Rocks, and there appeared to be good hope of the tow making the Bridge and passing through, she took a violent sheer to starboard, apparently forced by an eddy of overwhelming strength. Her forward end passed over the Platters, the ship's forefoot digging into the bank adjacent to and shoreward of the Rocks. This disastrous sheer occurred, and was concluded, in a matter of seconds".[5]

The Headmaster and his party had arrived on the Suspension Bridge and they watched the final moments as the sheer took control. "Conway's bluff brows swung over towards the shore … and carried her irresistibly across the Platters. We saw her masts cant and come upright again as her keel touched and then slipped over the rocks into deeper water, and then her stem touched the shore... the bows of the old ship kissed the shore so gently that I was convinced no damage could have been done." [6].

The very moment of impact is captured in this photo.

Captain Goddard, who had commanded the ship for many years and brought her safely from Liverpool to Bangor and then from Bangor to Plas Newydd thought otherwise "That is the end." he said.[6]

The Log Book records she grounded at 10.25 am[12]. (About 15 minutes before local High Water, or about two inches before the top of the tide on the very highest tide of the year) (Williams Note 14). Other reports confirm the gentleness of the impact. Cadet Owen Roberts, freed from his duties in the aft party, had come up on deck and was standing right behind Captain Hewitt, the pilot and Captain Miller "As we grounded Eric swayed forward and I swear he bit right through his cigarette.".[16] Whilst others attended to affairs of state, Owen, upholding the best traditions of Conway cadets went foraging. The galley was deserted but the range had shifted forward off its base. "Behind was the biggest pile of compacted dead cockroaches you could ever imagine"[16], enough to put him off his foraging!

|

|

|

Durrant continued : “As the tow lines eased momentarily, the ensuing and suddenly increased strain caused the Minegarth's 6" line to part, but her 8" line, plus the Dongarth's two hawsers connected direct to the Conway, continued to hold. The tugs were eased over to a position in which the hawsers were leading aft across the "Conway's" bows, and from where they continued their efforts to haul her stem off the bank. Those efforts were restricted by the necessity, and difficulty, of keeping the tugs head on to the racing tide, plus the very small radius of action available in the rocky channel” .[5]

As they began their struggle the pilot boat cast off and moved away from the ship. They continued pulling at full speed for another ten minutes, but, with no result.

On board Conway Captain Hewitt realised that she was hard ashore and at 10.45 am[12] ordered the tugs to let-go. They proceeded immediately to Menai Pier to await developments.

|

|

|

She was 1,100 feet away from the Suspension Bridge on a heading of 118°"[5]. |

|

|

Lt Cdr Brooke Smith immediately began taking soundings all around the ship as the pilot boat came back alongside. His findings were not encouraging, two thirds of the hull was safely on the Platters shelf but a third of her was unsupported and would be suspended over 31 feet of water at low water[5]. The tide was beginning to fall faster, only time would tell whether the strength of the construction would be able to support the huge loads that were already being applied to her.

"The strength of a ship. Let its construction be what it may, can never exceed that of its weakest parts." Sir Robert Seppings, the ship's designer and constructor in 1814.

These ships were phenomenally strong transversally with 13" square frames spaced only a couple of inches apart and clad inside and out with 13" thick planking, resulting in a shipside over 3 foot thick of what was virtually solid oak. This was further braced transversely by rows of deck beams at 7 ft vertical intervals and their oversize grown oak beam knees (wooden brackets) which extended to the deck below. So the shipside strength was massive - it was of course their armour against enemy cannon shot. But by contrast the keels of these ships were surprisingly puny. Tapering towards bow and stern and having a maximum section of only 19" square amidships, usually of elm, and made up of a maximum of eight lengths each not less than 25 ft long, which were simply laid over each other with scarfs (their ends cut with matching diagonal cuts) and fastened together with the regulation eight nails. Thus the keel contributed nothing at all to longitudinal strength. For this these ships are best thought of as a primitive compound girder, relying on the longitudinal planking of their multiple decks supported by a system of stanchions (posts), which together with their hull planking provided their only longitudinal rigidity, although Conway was stronger than most due to Seppings' revolutionary system of diagonal bracing [see plan] While all of this was said to be 'bolted' together, these 'bolts' did not have threads and nuts as we now think of bolts, but were no more than what today we would call nails (albeit typically an inch and a quarter in diameter) which were laboriously hammered into pre-drilled undersize holes. So these ships were notoriously weak longitudinally, and they must have worked abominably in a seaway. Indeed, to quote C. Napean Longridge ("The Anatomy of Nelson's ships"): "All of these ships started to hog (arch their 'backs') as soon as they took to the water."[14]

As the tide fell she was losing the vital support of the water. Cadet Noel Roberts clearly remembers the ominous creaks and groans that started almost as soon as she grounded.[18]

|

--Previous Section | Introduction | Next Section --

|

|